Don’t you just love this time of year? Things start to wind down, you get a moment to breathe, and then you gather round with those people you cherish and … decide if it’s time to burn your national soccer federation’s existing structure to the ground.

Happy Inquest Season, everyone!

It happens every four years. By definition, only one country can leave the World Cup with the title. Perhaps a couple of others with minimized expectations can also consider their trophy-less runs to be successful, but the majority of the 32 teams will head home feeling like failures. After Saturday’s 2-1 loss to France, some in the English media have already begun calling for “an inquest” into the federation’s shortcoming. And you can bet other calls-to-inquest are being harmonized in front of fireplaces across Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas.

I, however, am not a practicing Inquestador. I just like to watch with an ironic remove. Instead, I abide by the fact that soccer is incredibly random — and that what makes the World Cup so compelling is how it plays up the randomness, with so few matches, and those matches occurring only once every four years. This tournament isn’t designed to unearth the best national team in the world; no, it’s designed to create what we’ve seen so far: utter and complete chaos.

So, with that in mind, let’s take a look at all of the favorites (and the United States men’s national team) who have been eliminated and see if there’s anything they can do over the next four years to give themselves a slightly better chance at conquering the randomness.

USA: Can you find more dudes?

USA: Can you find more dudes?

The calls for Gregg Berhalter’s job during the World Cup were baffling to me. (OK, I’m not baffled; almost everyone hates their manager because of everything I just wrote.) The USMNT was the youngest team at the World Cup, they made the round of 16, and they went toe-to-toe with both England and the Netherlands.

The results won’t show it, but this was America’s best performance at a World Cup since America started qualifying for World Cups again in 1990. Most of that comes down to the massive increase at the top end of the talent pool, but Berhalter deserves plenty of credit, too. The manager’s job is to get the talent to play up to its capabilities, and that’s what happened in Qatar. This team did not underachieve.

Of course, you can convince yourself that they did underachieve… if you have a completely unrealistic understanding of how good the team’s players are. Ultimately, here’s what happened in Qatar: The US had nine players who were up to the requisite starting level of a team that makes a deep knockout-round run in the World Cup. In the starting XI, they were missing a second top-level center back next to Tim Ream, and then a third attacker between Christian Pulisic and Timothy Weah.

The bigger problem was the lack of depth. While the midfield was one of the best at the tournament, there was no fourth guy who could come on for Weston McKennie and maintain a similar level of performance. The same is true at fullback; Antonee Robinson played every minute of the tournament at left-back, while whoever replaced Sergino Dest was, well, a lot worse than Sergino Dest. Up top, Brenden Aaronson was ineffective off the bench, and when Gio Reyna finally got to play against the Netherlands, he too was totally ineffective.

The Reyna story then blew up over the weekend when Berhalter’s comments at something called the HOW Institute for Society’s Summit on Moral Leadership were made public. About one unnamed, under-performing player, he said, “We were ready to book a plane ticket home, that’s how extreme it was.” It was quickly revealed that this player was Reyna, and both staff and players were frustrated with his lack of effort in pre-tournament training. Given his, um, subdued performance in the Round of 16, it seems like Reyna wasn’t ready to contribute — for physical or emotional reasons, or both — in Qatar. That just massively exacerbated the team’s lack of depth.

This showed up, I think, in two ways. Firstly, the team faded in almost every second half — not because Berhalter refused to adjust, but because his good players got tired and the only options to replace them were, to put it simply, much worse at playing soccer. And since there was no depth across the roster, some of the stalwarts like Tyler Adams, Yunus Musah and Robinson were just totally gassed and made killer mental errors against the Netherlands.

We love to act like some brilliant manager can just magically come in, sprinkle some tactics and make all of our players better, but that’s just not how soccer works. Ultimately, talent is — by far — the most important driver of national team success. If the US wants to be better in 2026, they’re gonna need Aaronson to be better and Reyna to be back fit, as well as being fully reintegrated into the program. But they also need at least one other rotation fullback — Borussia Monchengladbach‘s Joe Scally, perhaps? — and at least one other top-level central midfielder — ??? — who can spell the starters and still provide quality minutes. In other words, the team in Qatar went nine deep. Get that up to 13 — or 15 — by 2024 and then the ceiling gets way higher and the manager can justifiably be held to a higher standard.

England: How do you handle this?

England: How do you handle this?

On the one hand, England did what they always do: get bounced in the quarterfinals. On the other hand, England probably outplayed the defending World Cup champs and totally shut down Kylian Mbappe.

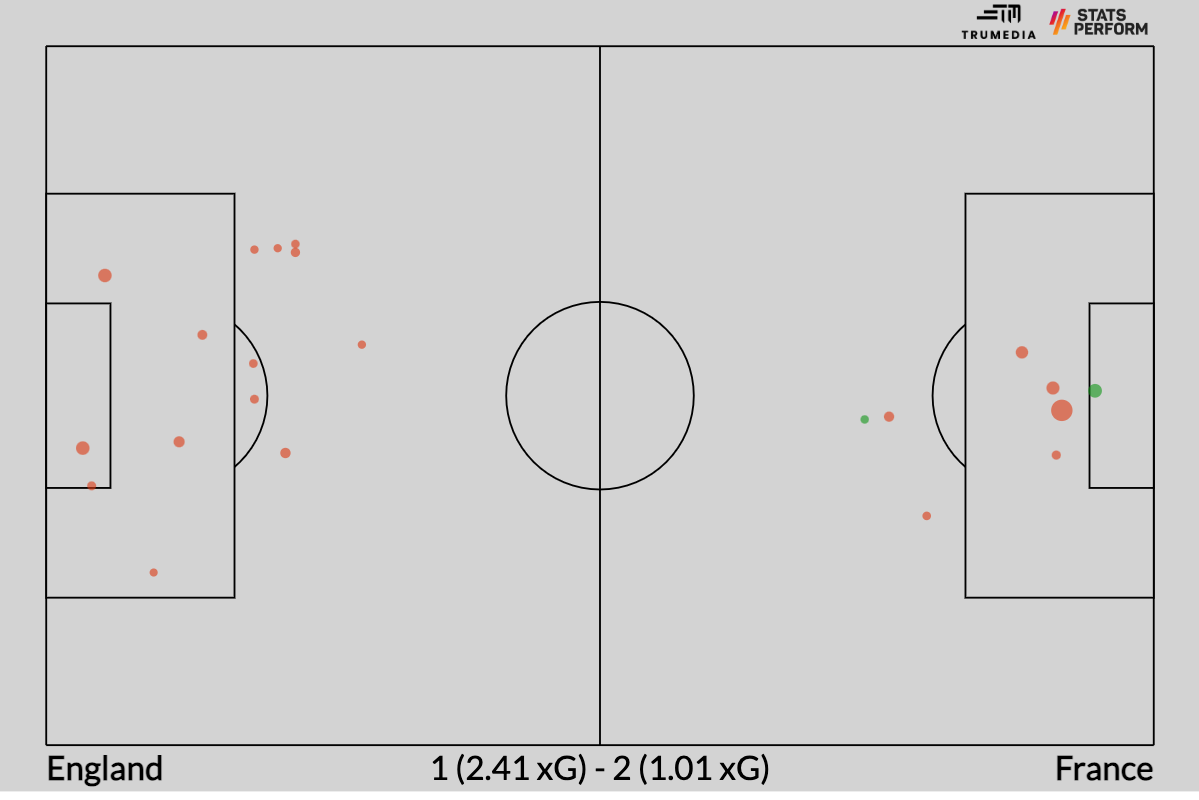

The match was relatively even when you strip out the penalties, I think, but England created enough constant pressure to create at least one of those penalties:

Ultimately, they lost because Hugo Lloris turned back the clock and made seven saves, Aurelien Tchouaméni hit the shot of his life, and Harry Kane — one of the best penalty takers in the world — smashed a penalty into the stands. In terms of controlling the controllable, England did that about as well as they could. There may have been a couple of little areas for improvement here and there; Raheem Sterling hasn’t played well in about eight months, while their inability to deploy Trent Alexander-Arnold‘s attacking talents still feels like a big miss. But compared to what we’ve seen across all of the other top teams, those seem like minor quibbles.

Most of the their key contributors are still in their 20s, and there’s all kinds of young talent that can pop up over the next four years. While I think England’s last two deep tournament runs were aided by some good fortune and some very easy draws, England were simply just really good in Qatar. Now, they might be able to attract one of the best coaches in the world to replace Gareth Southgate, but if they can’t, then there’s very little to suggest that what they’re currently doing isn’t working. After all, if you replace Southgate, there’s always the chance that someone comes in and isn’t as good.

Brazil: Do tiny edges matter when you have this much talent?

Brazil: Do tiny edges matter when you have this much talent?

I have the same opinion of Brazil that I had in 2018, when they were also eliminated in the quarterfinals: They’re the best team in the world.

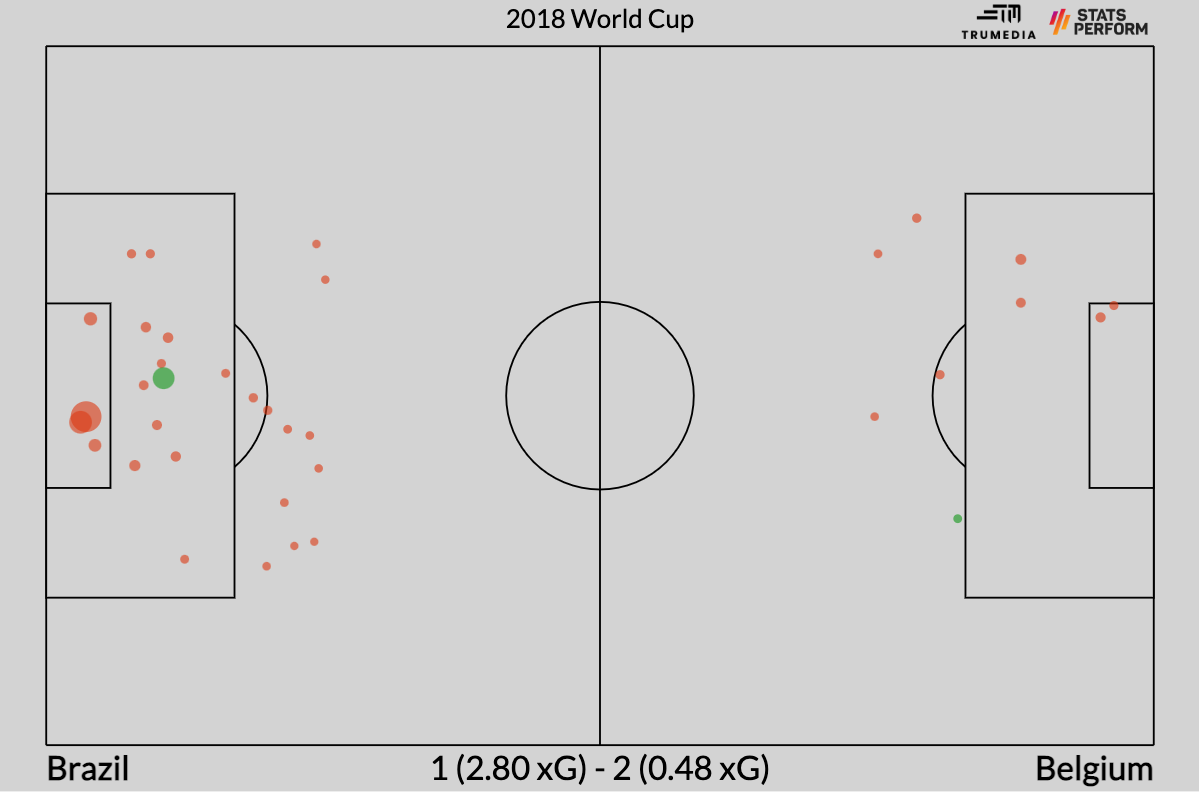

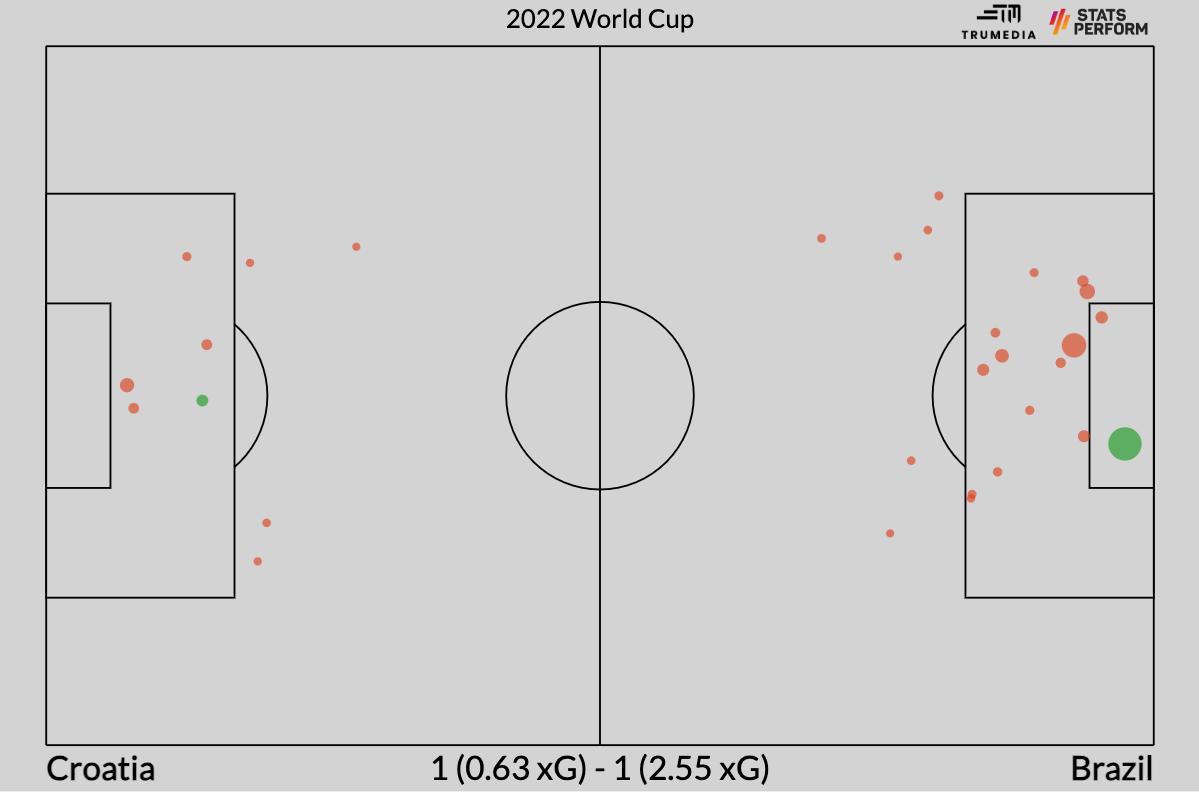

Here’s the loss to Belgium in 2018:

And here’s the draw-and-then-shootout-loss to Croatia:

The story here (just like last time) is that it’s really hard to kick a bouncing ball into a goal, even when you have maybe the most talented collection of attackers in the world doing the kicking. I’m sorry to keep simplifying down to the language of a 10-year-old, but that’s what these games are about. The results aren’t indicators of some national moral fiber or emotional strength or brilliant game-planning; sometimes the ball goes in, sometimes it doesn’t, and then one team gets to move on. May we all accept how silly these matches are.

Now, that being said, Tite managed Brazil (at times) like winning wasn’t the most important thing. That’s fine, of course. I don’t watch the World Cup because it’s a cold-blooded search for efficiency — and I doubt many people do. But I don’t know. The decision to bring 25-year-old Flamengo striker Pedro instead of Liverpool‘s Roberto Firmino felt like a “well, the 26th guy doesn’t matter” pick. Subbing third-string keeper Weverton on against South Korea was a nice moment to get minutes for everyone on the squad, but that change could’ve also been used to sub out and save some minutes for one of his star players. And then, against Croatia, taking out Vinicius Junior for Rodrygo — the former already a superstar for Real Madrid, the latter not even a full-time starter for the same team — so early into the match just seemed so bizarre in a lose-and-you-go-home game.

This was likely Neymar’s last World Cup at the peak of his powers, but I have no doubt that Brazil will be able to run out a team of almost equivalent, incredible talent in 20226. They’re so good … but not to the point that they’re immune to the effects of finishing variance. I wonder, though, how much they even care.

Portugal: Time to move on?

Portugal: Time to move on?

With the national team, Cristiano Ronaldo got caught between eras. He came into the picture — not yet the goal-scoring phenom — at the tail end of what was considered the country’s Golden Generation, headlined by Real Madrid’s Luis Figo. They lost the final of Euro 2004 to Greece — in Portugal — and then went out to France in the semis of the 2006 World Cup. Soon after, Ronaldo became the Ronaldo who went on to win five Ballon d’Ors, but the rest of the talent deteriorated around him. Although he went out injured in the finals against France, Ronaldo dragged a pretty mediocre team to a Euro 2016 title.

The Portugal team at the last World Cup was similarly unspectacular, and they went home after the round of 16. But then, a new generation of Portuguese stars bubbled up all across the field … right as Ronaldo was rapidly declining as a player. The last two major tournaments were ill-fitting attempts at melding an aging, increasingly immobile star with a dynamic collection of young talent that wants to be moving and interchanging and passing forward at every opportunity.

I was shocked that Fernando Santos dropped Ronaldo from the starting lineup. I was shocked it worked as well as it did against Switzerland. And I wasn’t shocked that it ground to a halt against Morocco, the most organized defensive side in the tournament.

These players have barely had any opportunities to play without Ronaldo and were essentially figuring it out on the fly at the freaking World Cup. In some ways, Portugal currently have another Golden Generation now, and I think it’s pretty clearly time for them to figure out how to do it on their own. Whether 37-year-old Ronaldo is willing to walk away and let that “zero knockout-round goals at the World Cup” bit of trivia hang over a legacy he so clearly cares deeply about? I’m not so sure.

Netherlands: Who will score the goals?

Netherlands: Who will score the goals?

Despite a run to the quarterfinals and taking Argentina all the way to penalties, the Netherlands created 0.86 expected goals per 90 minutes across their five matches at the World Cup. That’s only better than five teams. To add to that concern, their best attacker, Memphis Depay of Barcelona, will be 32 at the next World Cup.

Cody Gakpo scored three times in Qatar, but that came on five total shots worth just 0.31 xG. Gakpo did also lead the team in chances created (10) and expected assists (0.7), and he’s still only 23, but there’s no guarantee that he’s destined to become a star; there’s no guarantee he’s even destined to be a starter at the Premier League-level. He’s been tearing it up in the Dutch Eredivisie, but the transfer market is riddled with players who dominated amid the Eredivisie’s openness and struggled in a bigger league.

The point is: His future still carries a lot of uncertainty. I’m not confident he’ll be able to be The Guy in 2026.

Frankly, the Netherlands looked the most dangerous in Qatar when they threw on two gigantic forwards (Wout Weghorst, Luuk de Jong) and lumped the ball into Argentina’s box. That won’t be an effective or accepted tactic going forward. While there’s a lot of talent scattered throughout the rest of this squad, I don’t think their approach at this tournament is sustainable in any kind of long-term way.

Spain: RIP, tiki-taka?

Spain: RIP, tiki-taka?

For my book, “Net Gains: Inside the Beautiful Game’s Analytics Revolution,” Leeds manager Jesse Marsch talked to me about how he developed his theory toward a more muscular, more athletic, more vertical kind of soccer at the beginning of the previous decade:

The game was moving away from the Barcelona “pass pass pass pass” and it was moving more into playing in transition, good at counter-pressing, and playing more intensively. I just feel like athletes were getting faster and stronger. Barcelona were unique to that group of players, to that country and that club.

What drove me nuts about Barcelona’s football is that I loved watching it and it was amazing, but there was a 10-year phase in football when everyone was trying to play Barcelona football and nobody had the quality of players and the technical ability and the intelligence on the pitch of what La Masia [Barcelona’s academy] and what Barcelona had. So, it’s always about trying to make sure that whatever style of play you want, it matches the types of players you have.

While Marsch was talking about club teams across Europe, I wonder if it doesn’t also currently apply to the Spanish national team. What if the possession-dominant approach only worked because Spain had arguably the three-best midfield passers — Sergio Busquets, Xavi and Andres Iniesta — in the history of the sport? They then had reinforcements like Xabi Alonso, David Silva and Cesc Fabregas who are all also considered among the best midfielders of their generation. They were able to maintain possession to absurd degrees but then also turn it into enough dangerous opportunities at the other end.

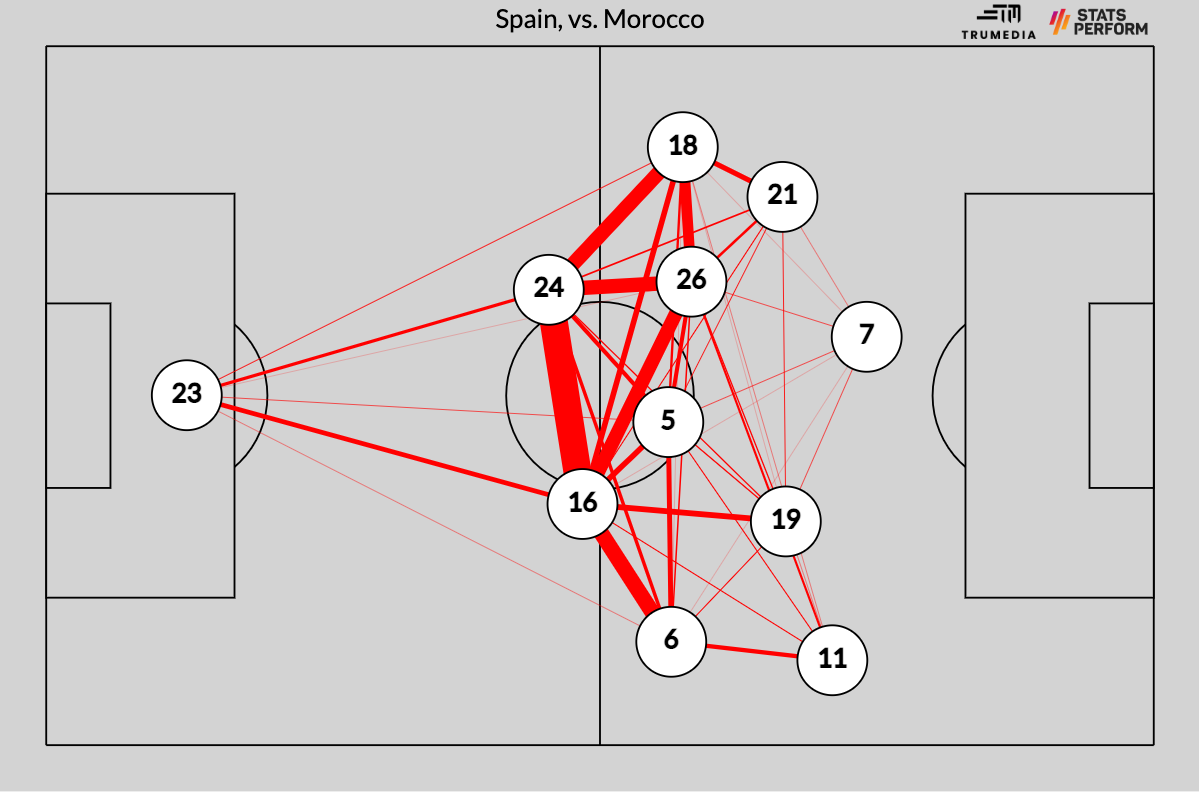

Luis Enrique’s Spain also dominated possession — mainly by having their center backs pass the ball back and forth.

Busquets is diminished at age 34, Pedri is fantastic, but is still not Iniesta, and Gavi — to my eyes — is an intriguing prospect who’s not even remotely close to a world-class player at this point in his career. (He’s 18, after all.) Beyond the midfield, the center-backs aren’t at the same level of years past, while the fullbacks are either not fullbacks or fullbacks who are well into their 30s. Up top, none of Enrique’s four main choices (Dani Olmo, Marco Asensio, Ferran Torres, Alvaro Morata) are even consistent starters for their club teams.

The talent isn’t what it used to be, and that’s the main reason for Spain’s early exit. But it certainly didn’t help that Spain’s strategy seemed completely oblivious to that fact. Can the next coach convince the federation and the fan base that, for the first time in forever, they might benefit from having a little less of the ball?

Germany: Does defense even matter?

Germany: Does defense even matter?

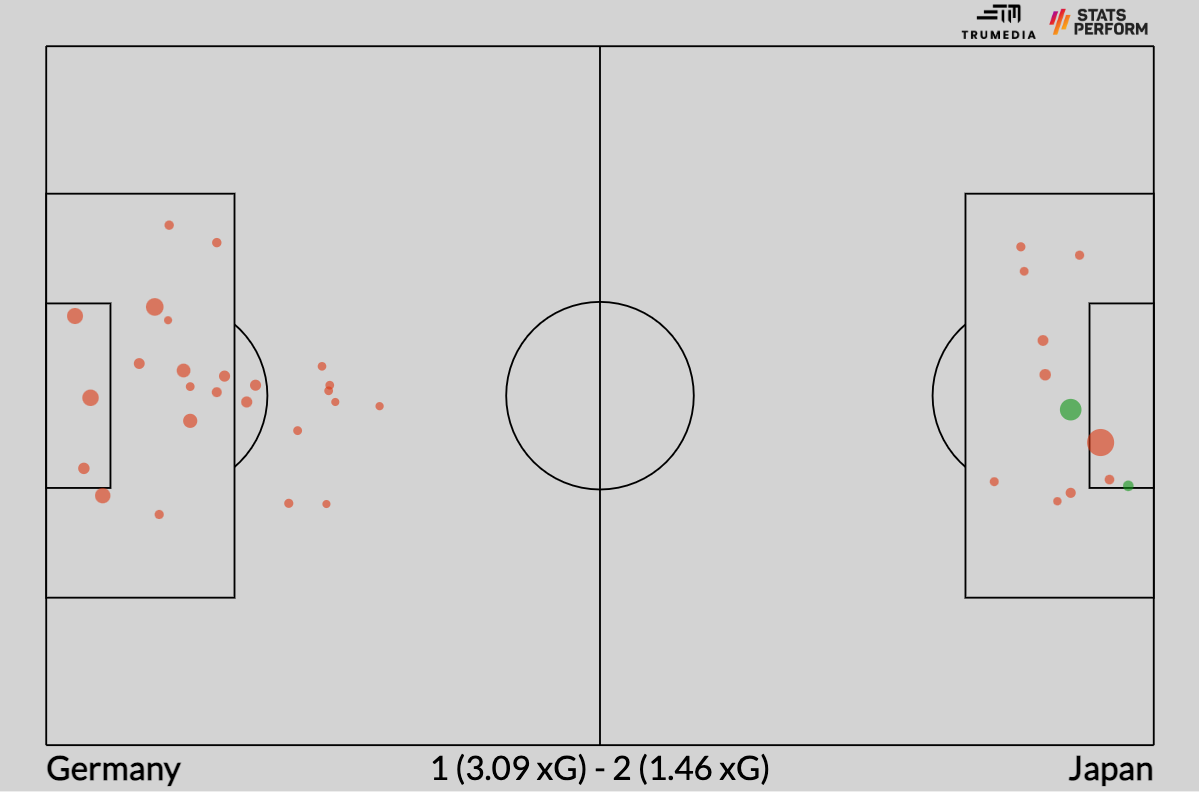

Despite being eliminated after three matches, Germany have still created more xG (10.15) than every team other than Brazil. Their World Cup ended for two reasons: 1) Spain beat Costa Rica 7-0, and 2) this happened against Japan:

I’m still not convinced that they weren’t one of the four or five best teams at the tournament. FiveThirtyEight’s model rates them as second-best behind Brazil, and their rating actually improved over the course of the tournament. Teams that play high-event games and dominate the balance of chances like Germany tend to be really good over the long run.

Of course, World Cup soccer doesn’t have a long run. You play a couple of games and then it’s over — no matter how good you are. It’s possible that manager Hansi Flick has pushed the dials too far toward “attack,” and that made Germany more susceptible to an upset. Among all teams, they were 11th in xG conceded per 90 minutes.

I broadly think Flick should stick with this style because it plays to the strengths of his players, who all play for attack-tilted club teams. But perhaps there’s a tiny personnel tweak he can make that just slightly lowers their attacking capacity, but improves the defense and makes a game like the Japan game a little bit less likely.

Belgium: Is this it?

Belgium: Is this it?

They might have one more World Cup with Kevin De Bruyne, maybe the best player in the history of the country. Keeper Thibaut Courtois should still be the starter in four years. And if Romelu Lukaku can stay healthy, he, too, will probably be around in 2026. But they’ll, respectively, be 35, 34, and 33 when that tournament rolls around. After that, they’ll likely have a collection of solid midtier European players and a handful of guys from the Belgian league filling out the rest of the roster.

The days of Belgium seriously challenging for international trophies are likely over.

Credit: Source link